Google Slides hotkeys help save time when creating presentations. They also help to optimize the user experience by simplifying numerous performance tasks. These shortcuts are a handy feature for navigation, formatting, and workflow control.

Read on to learn essential keyboard shortcuts you can master to elevate your Google Slides presentation skills.

List of Keyboard Shortcuts

To access a list of keyboard shortcuts on your computer, you can hit Ctrl+ / for Windows or Chrome-operated devices. Mac users can press Command+/.

Listed below are keyboard shortcuts for basic Google Slides functions:

- Ctrl+M (Windows/Chrome OS) or Command+M (macOS): Generate a new slide.

- Ctrl+C (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+C (macOS): Add selected information to the clipboard.

- Ctrl+D (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+D (macOS): Duplicates slides highlighted on the Filmstrip.

- Ctrl+X (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+X (macOS): Cut selected information to the clipboard.

- Ctrl+V (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+V (macOS): Paste copied content to a slide.

- Ctrl+Z (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+Z (macOS): Reverse an action.

- Ctrl+Y (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+Y (macOS): Repeat an operation.

- Ctrl+S (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+S (macOS): Save slide content.

- Ctrl+K (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+K (macOS): Insert or edit an external link.

- Ctrl+P (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+P (macOS): Print slide presentations.

- Ctrl+G (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+G (macOS): Find again.

- Ctrl+/ (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+/ (macOS): Show shortcuts.

- Alt+Enter (Windows/Chrome OS) or Options+Enter (macOS): Open a link.

- Ctrl+A (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+A (macOS): Select all.

- Ctrl+O (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+O (macOS): Triggers a pop-up that helps you open files from a drive or computer.

- Ctrl+F (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+F (macOS): Search and find text in your slide.

- Ctrl+H (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+H (macOS): Find and replace distinct content from your presentation.

- Ctrl+Shift+F (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+Shift+F (macOS): Transition to Compact mode. Ideal for hiding the menu.

- Ctrl +Shift+C (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+Shift+C (macOS): Enables caption use.

- Ctrl+Shift+A (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+Shift+A (macOS): Select none.

Keyboard Shortcuts for Formatting Google Slides

Google Slides offers a plethora of customization options to help perfect your presentation, including standard functions like italicizing, bolding, and underlining text.

Here are some essential keyboard shortcuts to help format your Google Slides:

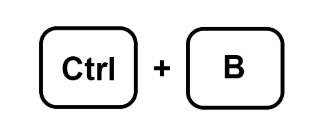

- Ctrl+B (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+B (macOS): Bold content.

- Ctrl+I (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+I (macOS): Italicize selected text.

- Ctrl+U (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+U (macOS): Underlining selected information within a slide.

- Alt+Shift+5 (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+Shift+X (macOS): Apply strikethrough to text.

- Ctrl+Shift+J (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+Shift+J (macOS): Apply justification alignment to text.

- Ctrl+Alt+C (Windows/Chrome OS) or Command+Option+C (macOS): Duplicate the format of selected text.

- Ctrl+Alt+V (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+Option+V (macOS): Paste text format.

- Ctrl+\ (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+\ (macOS): Delete text format.

- Ctrl+Shift+> and < (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+Shift+> and < (macOS): Adjust font size one point at a time.

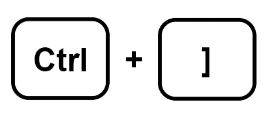

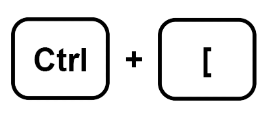

- Ctrl+] and [ (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+Shift+] and [ (macOS): Modify paragraph indentation.

- Ctrl+Shift+L (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+Shift+L (macOS): Apply left alignment to text.

- Ctrl+Shift+E (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+Shift+E (macOS): Center aligns content.

- Ctrl+Shift+R (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+Shift+R (macOS): Right align text.

- Ctrl+Shift+7 (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+Shift+7 (macOS): Insert numbered list in a slide.

- Ctrl+Shift+8 (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+Shift+8 (macOS): Add a bulleted list.

Filmstrip Usage

When working in Google Slides, a vertical pane to your left displays all your slides. This is what is referred to as a Filmstrip. You can use a few hotkeys to simplify your work when focusing on the pane.

Here are some of the essential shortcut functions:

- Ctr+Alt+Shift+F (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+Option+Shift+F (macOS): Shift focus to the Filmstrip.

- Ctrl+Alt+Shift+C (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+Option+Shift+C (macOS): Move focus to the slide.

- Up/Down Arrow (Windows/Chrome OS/macOS): Shift attention to the previous or next slide in a presentation.

- Home/End (Windows), Ctrl+Alt+Up/Down Arrow (Chrome OS), or Fn+Left/Right Arrow (macOS): Move the slide in focus up or down.

- Ctrl+Shift+Up/Down Arrow (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+Up/Down Arrow (macOS): Adjusts the slide in focus by moving it to the beginning or end of the presentation.

- Shift+Up/Down Arrow (Windows/Chrome OS/macOS): Extend the selection to the previous or next slide.

- Shift+Home/End (Windows) or Shift+Fn+Left/Right Arrow (macOS): Select the first or last slide.

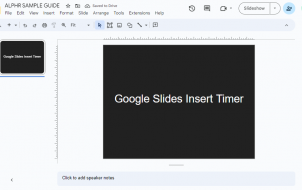

Accessing Menus on PC

This section will help if you’ve been looking for quick ways to access the menu options in Google Slides. Here are some of the hotkeys you can use:

- Alt+F (Chrome) or Alt+Shift+F (Other browsers): Opens File menu.

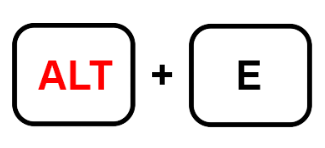

- Alt+E (Chrome) or Alt+Shift+E (Other browsers): Access the Edit menu.

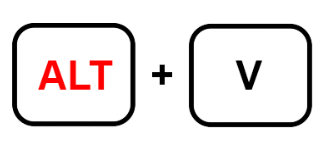

- Alt+V (Chrome) or Alt+Shift+V (Other browsers): View menu.

- Alt+I (Chrome) or Alt+Shift+I (Other browsers): Access the Insert menu.

- Alt+O (Chrome) or Alt+Shift+O (Other browsers): Opens the Format menu.

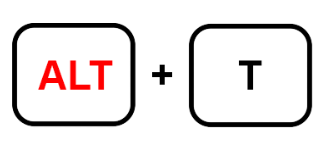

- Alt+T (Chrome) or Alt+Shift+T (Other browsers): Opens the Tool menu.

- Alt+H (Chrome) or Alt+Shift+H (Other browsers): Access the Help menu.

- Alt+A (Chrome) or Alt+Shift+A (Other browsers): Opens the Accessibility menu. Note that you can only access this when the screen reader support feature is enabled.

- Shift+Right-click: Displays your browser’s context menu. Google Slides, by default, hides this menu immediately after it’s launched.

Using MacOS Menus

You can also use a few keyboard shortcut keys to access the Mac menu bar

- Ctrl+Option+F: Access the File menu.

- Ctrl+Option+E: Open the Edit menu.

- Ctrl+Option+V: View menu

- Ctrl+Option+I: Access the Insert menu.

- Ctrl+Option+O: Open the Format menu.

- Ctrl+Option+T: Tools menu

- Ctrl+Option+Help: Access the Help menu.

- Ctrl+Option+A: Opens the Accessibility menu.

- Cmd+Option+Shift+K: Access the Input Tools menu. This option is only available for documents that contain non-Latin languages.

- Shift+Right-click: Shows browsers context menu

Using Comments

Comments are an essential element within Google Slide presentations. They aid in communication and enhance interaction.

- Ctrl+Alt+M (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+Options+M (macOS): Insert comment

- Ctrl+Enter (Windows/Chrome OS/macOS): Enter current comment.

- J (Windows/Chrome OS/macOS): Next comment.

- K (Windows/Chrome OS/macOS): Previous comment.

- R (Windows/Chrome OS/macOS): Reply to comment.

- E (Windows/Chrome OS/macOS): Resolve comment.

- Ctrl+Shift+Alt+A (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+Option+Shift+A (macOS): Open comment discussion thread.

Navigating a Presentation

You don’t have to touch your mouse to navigate your document during a presentation. Shortcut keys can help you streamline your presentation process and improve your workflow significantly.

Here are some hotkeys to help you ace that presentation:

- Ctrl+Alt and +/- (Windows/Chrome OS), or Cmd+Option and +/- (macOS): Helps you zoom a slide inward or outward.

- Ctrl+Alt+Shift+S (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+Option+Shift+S (macOS): Access the speaker notes panel.

- Ctrl+Shift+Alt+P (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+Option+Shift+P (macOS): Provides an HTML view of your presentation.

- Ctrl+Alt+Shift+B (Windows/Chrome OS) or Cmd+Option+Shift+B (macOS): Opens a slide’s transition animation panel.

- Ctrl+F5 (Windows), Ctrl+Search+5 (Chrome OS), or Cmd+Enter (macOS): Displays slides from the currently selected slide.

- Ctrl+Shift+F5 (Windows), Ctrl+Search+5 (Chrome OS), or Cmd+Shift+Enter (macOS): Displays slides from the first slide.

- Right/Left Arrow (Windows/Chrome OS/macOS): Move to the next slide.

- A number followed by Enter (Windows/Chrome OS/ macOS): This goes to the specific slide number you input.

- S (Windows/Chrome OS/macOS): Access speaker notes.

- A (Windows/Chrome OS/macOS): Open audience tools.

- L (Windows/Chrome OS/macOS): Toggle the laser pointer.

- F11 (Windows/Chrome OS) and Cmd+Shift+F (macOS): Enable full screen.

- B (Windows/Chrome OS/macOS): Display or return from a blank back slide.

- W (Windows/Chrome OS/macOS): Show or return from a white blank slide.

Master Your Google Slides

Learning how to use shortcut keys in Google Slides reflects positively on your professionalism. It also helps you to easily maneuver through a presentation without much hassle. If you frequently use this program then grasping these basic operations will significantly elevate your productivity.

Do you use keyboard shortcuts in Google Slides? Which hotkeys are most helpful in day-to-day Google Slides operations? Let us know in the comments section below.

Disclaimer: Some pages on this site may include an affiliate link. This does not effect our editorial in any way.