Roblox offers creative and unique ways to create worlds. If you want to share your gaming experience on Roblox and any of its games, adding a friend is the way to go. You can add friends on Roblox in various ways, depending on your device. Furthermore, you can add anyone you’d like to play with, from your friends from real life to someone you met while gaming.

By adding friends on Roblox, you can enjoy playing together on a single server, on multiplayer Roblox, or just chatting and getting to know each other while exploring worlds. Read on to learn how to add friends on Roblox on PC, console, or mobile device.

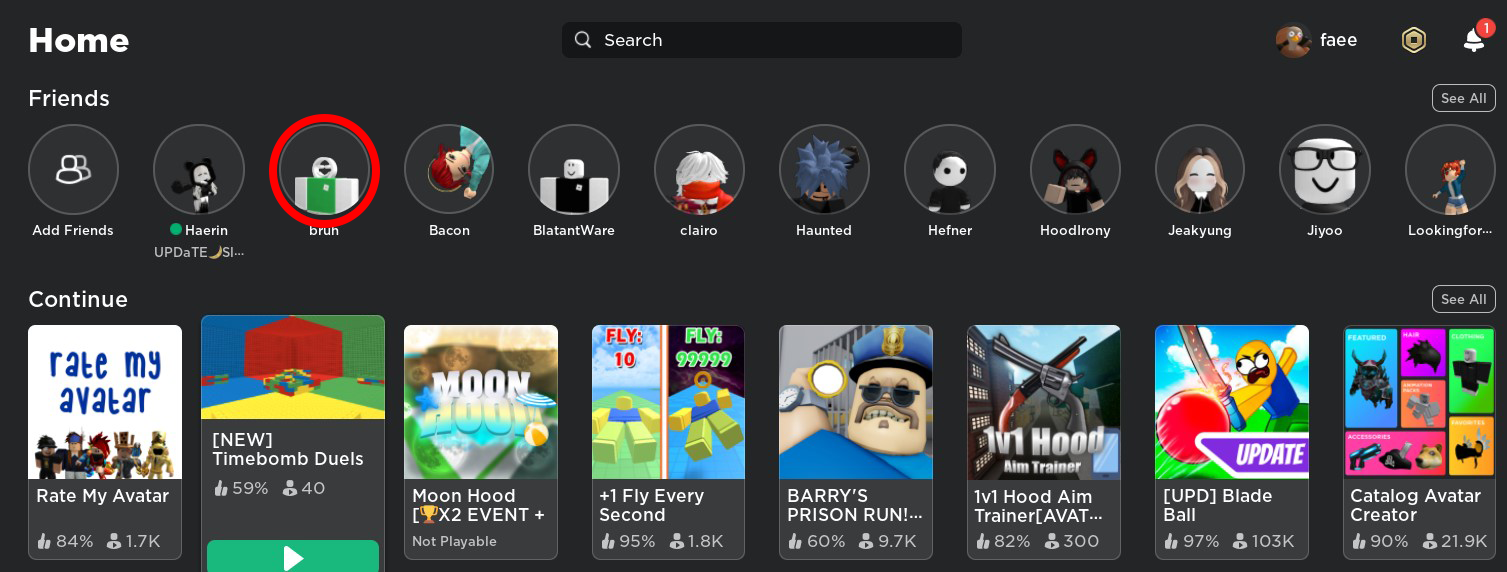

Adding Friends on Roblox

If you want to experience Roblox with friends, you can add them by typing their username in the search button and sending them a friend request. Navigating to the search button and adding a friend will differ depending on your device.

Adding Friends on PC

If you’re gaming on your computer, you can make new friends and send a friend request from the Roblox homepage or while in the game. This is how you can add someone from the gaming platform:

- Open the homepage and log in.

- Tap the three horizontal lines to open the menu, which will open on the left of the screen.

- Click on the “Friends” option.

- Type your friend’s name in the search box at the top of the screen.

- Click on “Enter.”

- Tap “Add Friend” when you locate the one you want to add from the list of options.

When you type your friend’s nickname, it’s essential to search for them in the option “in People.” After you type their username in the search bar, many options like Experiences, Avatar Shop, Groups, Creator Marketplace, and People will appear.

Another way of adding friends on PC while using Roblox is to send them requests in-game. This is a straightforward way of expanding your friend list, so if you meet a new player and want to continue playing with them, you can add them instantly. This is how you can go on about it:

- Click on the game you want to play.

- Join the server.

- While in the game, tap the “Esc” button on your keyboard.

- In the menu, click on the “Players” section.

- Next to the user’s nickname, click on the “Add Friend” option.

Adding Friends on Mobile Phone

You can also add new friends using your mobile device. You can add friends from the Roblox homepage if you’re using an Android, iPhone, or any other mobile phone. This is how you can do that:

- Open Roblox Mobile.

- Click on the icon with three horizontal dots at the screen’s bottom.

- Tap on the “Friends” option.

- Tap on the icon for the search feature.

- Enter the name of the person you want to add.

- Select “Return” if you’re using an iOS device. Or tap the button with a horizontal arrow on your keyboard if you use Android mobile devices.

- People with the same nickname you entered will appear. Select the person you want and tap “Add.”

If you’ve successfully followed these steps, under your friend’s name, instead of “Add,” it will show “Pending.”

Adding Friends on a Console

Currently, the only console where you can use Roblox is the Xbox, but there is no direct way to add friends from it. If you’re playing on Xbox, you can see all the friends in the “Friends” section, but there is no “Add Friend” button. However, there is a solution to this. You can open Microsoft Edge on your console and add friends to Roblox from there.

- Open the Xbox dashboard.

- Select the option “My games & apps.”

- Go to “See all.”

- Open your apps.

- Find the Microsoft Edge browser and open it.

- Open the Roblox homepage and log in.

- Navigate to the menu and select “Friends.”

- Type the nickname of a person you want to add.

- Search for them “in People.”

- Click on “Add Friend” under your friend’s name.

You can’t click on the same button to cancel your friend request if you send it to the wrong person. However, if that happens, the other player will probably decline your request, and you’ll be notified. The same goes if someone accepts the request. You get notifications regardless of the device you’re using to play Roblox games, so it’s futile to spam people with multiple requests.

Users can also include notes with their requests for scenarios where they need to jog the other person’s memory or just want to include a funny message.

How to See My Pending Friend Requests

Whether you’re using PC, console, or mobile device, you can see your pending friend requests in the same place. This is how you can navigate to it:

- Open the Roblox homepage.

- Click on the three horizontal stripes to open the menu.

- Next to the “Friends” option, you can see the number of pending friend requests.

- Click the option to see who sent them.

- You can accept, decline or ignore the request.

However, you don’t have any new requests if there is no number next to the “Friends” option.

How to Create an Alias for Roblox Friends

You can set your own nickname for your friends by using the option “Alias.” This is useful when a friend changes their nickname; you’ll still have their alias only visible to you to recognize them. Follow these steps to set up this feature:

- Go to your friend’s profile.

- In the “About” section, you can see the “Alias” feature. Click on the edit icon.

- Type in whatever you want your friend to be called.

- Tap on “Save.”

While you’re chatting with them, their alias will be in parentheses next to their username.

FAQs

Why can’t I find friends on Roblox?

You can’t find or add more friends on Roblox if you’ve reached the 200-friend limit. To find a new one, you have to delete someone. The other reason why this problem might occur is if you block a particular player. To add them to your friend list, you must first unblock them.

How do you find people in your contacts on Roblox?

You can sync your contacts and Roblox with Contact Importer. With this feature, other users who know you in real life and have your phone number can find you more easily. Finding friends by uploading your contacts will only work with users who also have this option turned on and contacts synced.

How do you join people who aren’t your friends on Roblox?

If you want to join someone who isn’t your friend, check their “Who can join me in experiences?” option. If this option is set to “Everyone,” you can join. However, if this option is “Friends, users I follow, and my followers,” you must follow that person by going to their profile.

Play Roblox Games With Friends

Every game is better with friends. Sharing gaming experiences and exploring worlds in Roblox with someone you know from real life or someone you met online can be fun. Roblox allows you to add friends on various devices, send personal notes, set aliases for them, and more.

Do you play Roblox games with friends or alone? Which device do you use for Roblox? Let us know in the comments section below.

Disclaimer: Some pages on this site may include an affiliate link. This does not effect our editorial in any way.