You’ve bravely fought through the underworld and conquered the Wall of Flesh. And now that you’ve entered Hardmode, you might be looking for a way to take off and soar. Terraria rewards your efforts with a cool craftable or accessory – wings, but there are also special wing types to find in the world.

This guide will tell you all you need to know about getting wings in Terraria and how they can make your game more fun.

Earn Your Pair of Wings

Wings aren’t for just everyone. Before you can get your first pair of wings, you’ll need to explore and conquer the world of Terraria, except for the Fledgling Wings, which will get their spotlight, too.

- To gain access to wings, you’ll need to be in Hardmode. If you’re not there yet, defeating the Wall of Flesh is the way in.

- Once in Hardmode,get to a Floating Island or Sky Bridge and wait for Wyverns to appear.

- Defeat the Wyverns to collect Souls of Flight. You’ll need 20 of these for your wings.

- Wings come in multiple shapes, so depending on the type of wings you want, you’ll need extra materials like Feathers, Souls of Light, or Souls of Night.

- When you collect all the materials, use a Mythril or Orichalcum Anvil to craft the wings.

Types of Craftable Wings and Their Crafting Materials

Here are just a few popular wing types that you can craft and how to make them.

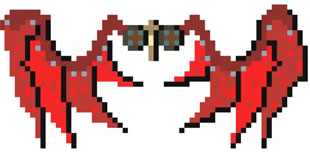

Demon Wings

To get the spooky Demon wings, along with the Souls of Flight, you’ll also need Souls of Night. You can gather these souls when you slay enemies in the Hardmode’s Crimson Corruption. To craft the Demon wings, you need to gather 20 Souls of Flight, 25 Souls of Night, and 10 feathers from Harpies. Once you have all the materials, head over to a Mythril Anvil to get your wings.

Angel Wings

On the other hand, to get the divine Angel wings, you’ll need Souls of Light. Enter the Underground Hallow and slay the illuminants there to collect the Souls of Light. Mix 20 Souls of Flight, the Souls of Light, and 10 Feathers together at a Mythril Anvil to craft Angel Wings.

Fairy Wings

Fairies are majestic, mystical creatures, and you can steal their wings. Return to the Hallow and slay the fairies there. This will reward you with Pixie Dust, as each fairy drops between one and five of this resource. Mix 100 drops of Pixie Dust and 20 Souls of Flight, and you’ll have Fairy Wings.

Sparkly Wings

Defeat Ocram to get 20 Souls of Blight. Combine them with ten feathers to craft a pair of Sparkly Wings. This tip is only for the Mobile and Console versions of Terraria. If you’re having trouble finding the ingredients, seek help from the Dryad. She’ll gladly sell you a pair for 40 Gold on Blood Moon nights.

Bee Wings

You can don these wings to pretend to be a buzzing bee, but they take some effort to craft. You need 20 Souls of Flight and 1 Tattered Bee Wing for this. The Tattered Bee Wing is a rare item drop that you can only get by battling Moss Hornets in the Underground Jungle. Although it’s not an easy find, you’ll be rewarded with this item if you defeat enough of these creatures.

Special, Unlockable, and Advanced Wings

Once you understand the fundamentals of flight, branch out to more wing types with unique abilities, as it’s not just their visuals that set wing pairs apart. Hovering wings give you a different way to fly and explore, while wings with an extended flight time or increased speed can take you flying farther for longer, reaching new locations quickly.

Also, many wing types are enemy drops or purchase-only, so you cannot craft them yourself. You must acquire them. Here are some interesting wing types to look into.

Leaf Wings

You can buy these wings from the Witch Doctor for one platinum coin and 50 gold coins when he is in the Jungle at night. After an update to the game, you can only buy Leaf Wings from him after defeating Plantera.

Steampunk Wings

The Steampunker will sell this unique pair of wings for a Platinum Coin after you defeat the Golem boss. The Steampunk Wings are comparable to Tattered Fairy Wings, Spooky Wings, and Betsy’s Wings in performance but are not as good as the Fishron Wings.

Fishron Wings

The Fishron Wings are a special set of wings that can only appear after you beat Duke Fishron. They can propel you forward much faster when flying over liquids. They also create a blue bubble trail for those playing from below as you speed through the water.

Compared to other accessories such as the Moon Shell, Neptune’s Shell, and Flipper, the Fishron Wings stand out when braving aquatic environments. While these other items may struggle in honey, the Fishron Wings don’t. They let you move through it easily.

Fledgling Wings

Most wings are a reward for hardcore players. They make you feel powerful and liberated after long, possibly grueling fights. But not all wings are for pros only. You’ll receive your first set of Fledgling wings when you start playing Journey Mode. There are also more wings to find in Skyware Chests, Sky Crates, and Azure Crates when playing on a PC, consoler mobile device, or the tModLoader version.

The Wing Mechanics

Press and hold the Jump key to fly temporarily after equipping the wings. You can rest and reset your flight time on solid blocks or climbing items like Ropes, Hooks, Shoe Spikes, or Climbing Claws. Some wing types also hover at particular heights if you hold Down and accelerate the ascent if you press Up. Once your flight time ends, you can keep holding Jump to glide. To speed up your gliding fall speed, press and hold Down.

Wings protect the player from falling, which overrides the Lucky Horseshoe and other fall damage-reducing items. However, the Stoned debuff can still cause you to take damage when falling.

Wings make you more stable and agile while flying than Rocket Boots, Spectre Boots, or other accessories alone. Wings enable you to fly farther. But wings still stack with the flight range of Rocket Boots and its upgrades. You can even use Cloud in a Bottle to get an extra jump after all your flight time expires.

Dyeing Your Wings

In Terraria, you can give wings an extra spark by dying them. Dyeing your wings is a great way to personalize them and make them fit your vision for your character’s appearance.

On the note of dyeing, the Jetpack’s particle effect will give off orange light even when dyed, and the Vortex Booster emits teal light. Other wings that have glowing effects may also change color depending on their dyes. And since wings in vanity slots no longer glow in version 1.4, those who want to stay invisible can take advantage of this.

Spread Your Wings and Fly

Wings are a reflection of your hard work and dedication to the game. They let you traverse harder areas to explore new places, battle formidable foes, and express yourself. If you’ve spent dozens of hours honing your skills or you’re just getting started in Terraria, wings can give you a well-deserved edge.

Did you discover any other wing types in Terraria not mentioned here? Do you have a favorite pair of wings? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Disclaimer: Some pages on this site may include an affiliate link. This does not effect our editorial in any way.