If you have some irreplaceable items in your Terraria inventory, like that trusty sword that’s taken you through thick and thin or a stack of potions you always want to keep close, you probably want to make them easy to access. Marking these items as favorite is the way to go, as this will make them always at hand.

This guide will show you how to mark those items as favorites so you can quickly whip them up when you need them most.

How To Favorite Items in Terraria

Since each platform uses a different input method, the way you favorite items depends on the platform you’re using.

PC (Mouse and Keyboard Input)

If you’re playing on a PC and using the mouse and keyboard rather than a controller, you should do the following:

- Bring up your Inventory with Esc.

- Hold down ALT on your keyboard, and Left-Click an item to add it to your favorites.

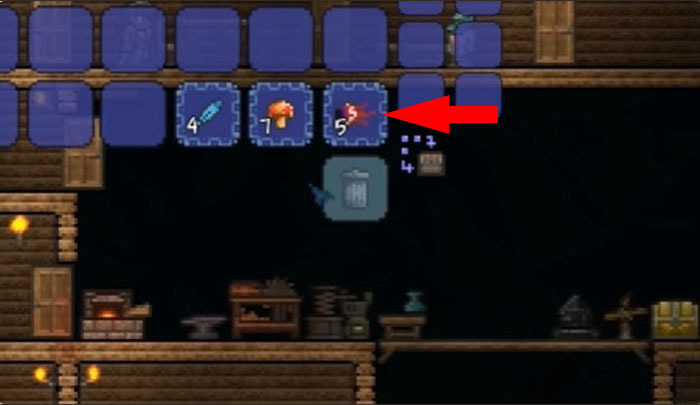

- Make sure the item’s frame has changed to verify that you favorited it.

You’ll see a sparkly border around an item when you favorite it. That’s your sign that this item has been selected. You can then go ahead and equip it whenever you want. But watch out because it will lose its favorite status if you move it back into the Inventory. If this happens, just give it another Alt+ Left Click to bring the VIP status back.

PlayStation and Xbox

The favorites feature works a bit differently on consoles than it does on the PC. There is no typical “favorites” feature in this version of Terraria, but you can add items to a hotkey, which functionally serves the same purpose.

If you’re playing on a PlayStation or XBOX console, try this to add an item to the hotkey:

- Open the Inventory with the Triangle button for PlayStation and Y button on XBOX.

- Pick an item from your Inventory to assign to the D-pad.

- Choose where on the D-Pad you want to put the chosen item.

Think of the D-Pad hotkey slots as a substitute for favorites. They’re not quite the same thing, but still keep some of your go-to items close at hand.

Nintendo Switch

Like the Sony and Microsoft consoles, the typical PC-style favorites aren’t available on the Nintendo Switch, either. But just as with these consoles, you have alternatives. This time, rather than assigning your most used items to the D-Pad, you add them to the (admittedly more versatile) Radial menu on your Hotbar. To do this:

- Open your Hotbar by holding the right bumper.

- Point to the item you wish to add with the analog stick.

- Release the stick, and the item should appear in your Radial menu.

A neat thing about the Nintendo Switch version’s Hotbar is that it can hold up to 10 items at once.

A Note on Mobile

It’s worth mentioning that at this time, the mobile version of Terraria does not offer the favorites feature nor a console-like equivalent. However, this might change, so keep your eyes out for updates.

Why Favorite Items

It’s unnecessary to favorite items, but once you try this feature, you will likely never want to play without using it again. The most apparent advantage of favoriting items is quick access. It bypasses the Inventory and lets you use an item straight away.

But this isn’t the only benefit in Terraria. The game safeguards your favorite items and treats them as essential. That means when you favorite an item, it won’t be possible to deposit or trash it by accident, so you can always access your most valuable and frequently used items.

If you’re digging and need to quickly move out blocks or resources, having pickaxes, torches, and potions as favorites will help avoid accidentally putting them into a chest. Conversely, you can temporarily un-favorite certain items when building or crafting for easier stacking.

What Items Should You Favorite

There are a few items you should always have on hand. Weapons and tools you can rely on in any situation (such as a sword or a shovel), ammunition for battling, and bait for fishing will make your gameplay much snappier. Favoriting these items means taking them out in a pinch with no downtime.

More “passive” items are also worth favoriting. Accessories like clocks or danger indicators, torches for exploring dark places, and potions to give you an edge in combat; all these items on hand mean less time spent on menus and more time spent exploring and playing.

Other Ways to Organize Your Inventory

One simple alternative way to organize your Inventory is to assign separate chests for various items. This way, you can store potions in one chest, weapons in another, and vanity items in a third. This method organizes your stuff better and makes finding whatever item you need easier in a pinch.

There’s also the “Sort Inventory” button—it’s a great tool that quickly tidies up your Inventory. Although it won’t give you the same safeguards against accidental deletion or relocation as favoriting does, it’s still effective at keeping things neat.

Tips and Tricks for Inventory Management

Favoriting items can definitely make it much easier to play, but that’s just the beginning of inventory management. Here are some extra tips to get the most out of your Inventory:

- Take advantage of the “Quick Stack to Nearby Chests” feature. It’ll quickly deposit items into fitting nearby chests.

- Use the “Restock” button to quickly replenish consumable items from your chests.

- Try the “Deposit All” feature when you want to empty your Inventory. Be careful with this one, though, because it will deposit all non-favorited items.

FAQ

Can I favorite items in multiplayer?

You can favorite items in both single-player and multiplayer. The steps are the same – it’s just a matter of picking your item and saving it for later.

Do favorited items transfer if I switch characters?

If you switch characters, your favorite items won’t come with you. You’ll need to select them again for that character.

Can I sort favorited items in a particular order automatically?

You can’t sort favorited items automatically, but you can manually arrange them in your Inventory in whatever way you prefer.

Can I favorite blocks or materials, or is it just for weapons and potions?

On PC, you can mark any item in your Inventory as a favorite. That includes blocks and items such as materials, weapons, and potions.

Favorite Wisely

Terraria lets you bookmark your favorite items easily, which is indispensable for such an inventory-focused game. Favorites are like an exclusive storage space for the things you use or treasure the most. Favoriting your most useful items saves time and effort. For any type of player, be it a fighter or builder, having the right items easily available can make all the difference. Making items favorite is a little different for PC and console players, but all these platforms, save for the mobile, take advantage of a version of this feature.

Which items in Terraria do you find the most valuable and worthy of favoriting? Do you have any other tips or tricks for managing your Inventory in Terraria? Drop a comment in the comment section below and share your thoughts.

Disclaimer: Some pages on this site may include an affiliate link. This does not effect our editorial in any way.