Sims 4 possibilities extend well beyond modifying your character’s appearance – you can also decide on their personality, hobbies, and career. One of the most entertaining skills is, perhaps, songwriting. Read on to find out how to teach your Sims to produce music.

In this guide, we will explain how to write songs in Sims 4 on PC and consoles using different instruments. If you want to not only make music but also earn a living with it, you will find instructions on how to do that, too. Additionally, we will answer some of the most common questions related to songwriting in Sims 4.

How to Write Songs in Sims 4?

First, let’s take a look at the basic requirements to make music in Sims 4. Here’s what you have to do to start writing songs in the game:

- Navigate to the catalog and purchase any musical instrument.

- Reach level eight of the instrument skill by playing it to unlock the songwriting option.

- Interact with the instrument and select Write Song.

Tip: in the base game, only guitar, violin, and piano are available. To sing, you need the City Living expansion. To unlock DJ mixing, you need the Get Together expansion. For media production, the Get Famous expansion is required.

How to Write Songs in Sims 4 Base Game?

Regardless of the device you’re playing Sims 4 on, find detailed instructions on how to write a song below:

- Navigate to your musical instrument and click on it.

- Select Write Song among suggested options.

- Choose a song among suggested. The higher is your skill level, the more options are available.

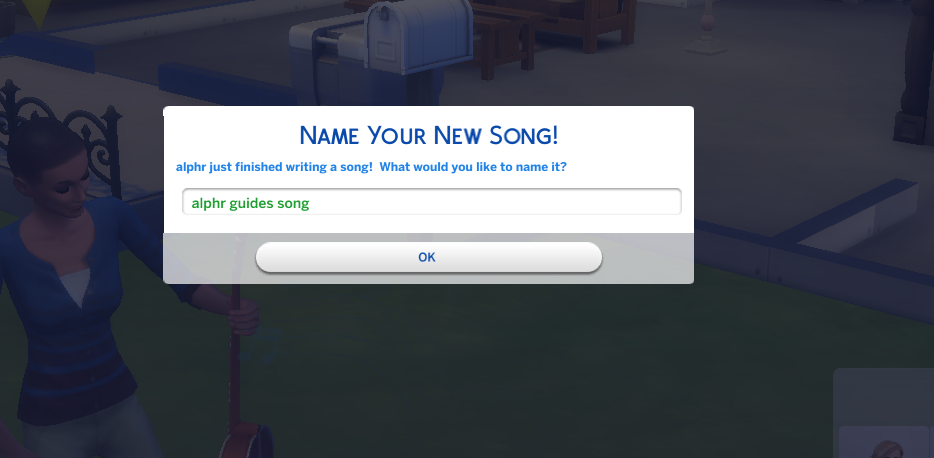

- Once you finish the song, type in the song name and hit Ok.

- You can play the song at any time by clicking on the instrument and selecting the Play option.

- To license your song, reach level nine of instrument skill.

Tip: make sure all needs of your Sim are fulfilled before you start, as writing a song is a long process.

Tip: if you stop during the songwriting process, the draft of the song will be saved. To resume, navigate to your inventory and click on the song sheet icon. You may have several drafts at once – in this case, choose the song you want to continue writing.

How to Write Licensed Songs in Sims 4?

If you want to earn money by making music in Sims 4, you have to license your songs. To do that, follow the instructions below:

- Write a song and make sure you have reached level nine of musical instrument skill.

- Navigate to the mailbox of your Sim and click on it.

- Select License Song, then choose an instrument and a song among suggested.

- You will start getting royalty payments the next morning.

- Payments last for a week. During this period, you won’t be able to write songs using the same instrument.

How to Write Songs and Get Famous in Sims 4?

If royalty payments aren’t enough to fulfill your ambitions, you can try to get famous in Sims 4. To do that, you need to purchase the Get Famous expansion. Follow the instructions below to raise your chances of becoming a popular musician:

- Master your media production skill by producing and remixing music tracks.

- Once you reach level five of the media production skill and have a finished song, you can release it to radio stations. Navigate to your inventory and select the Release Track option.

- You will gain fame with every song released.

- Optionally, send your songs to a record label to gain even more fame. To sign with a label, you have to produce new songs every day.

How to Sing in Sims 4?

To sing in Sims 4, you have to purchase the City Living expansion. Follow the steps below to write song lyrics in the game:

- Start practicing singing in karaoke or in the shower.

- Once you reach the second level of singing skill, you will be able to practice with a microphone or by simply clicking on your Sim.

- Once you reach level eight of the singing skill, you will be able to select the Write Lyrics option to record the vocal part of a song.

Tip: if you’d like to sing and play an instrument at the same time, you need to reach at least level three of instrument skill and level two of singing skill.

How to Write Songs Faster in Sims 4?

Leveling up your musical skills in Sims 4 is a time-consuming process. You can speed it up with the use of cheats. To do that, follow the instructions below:

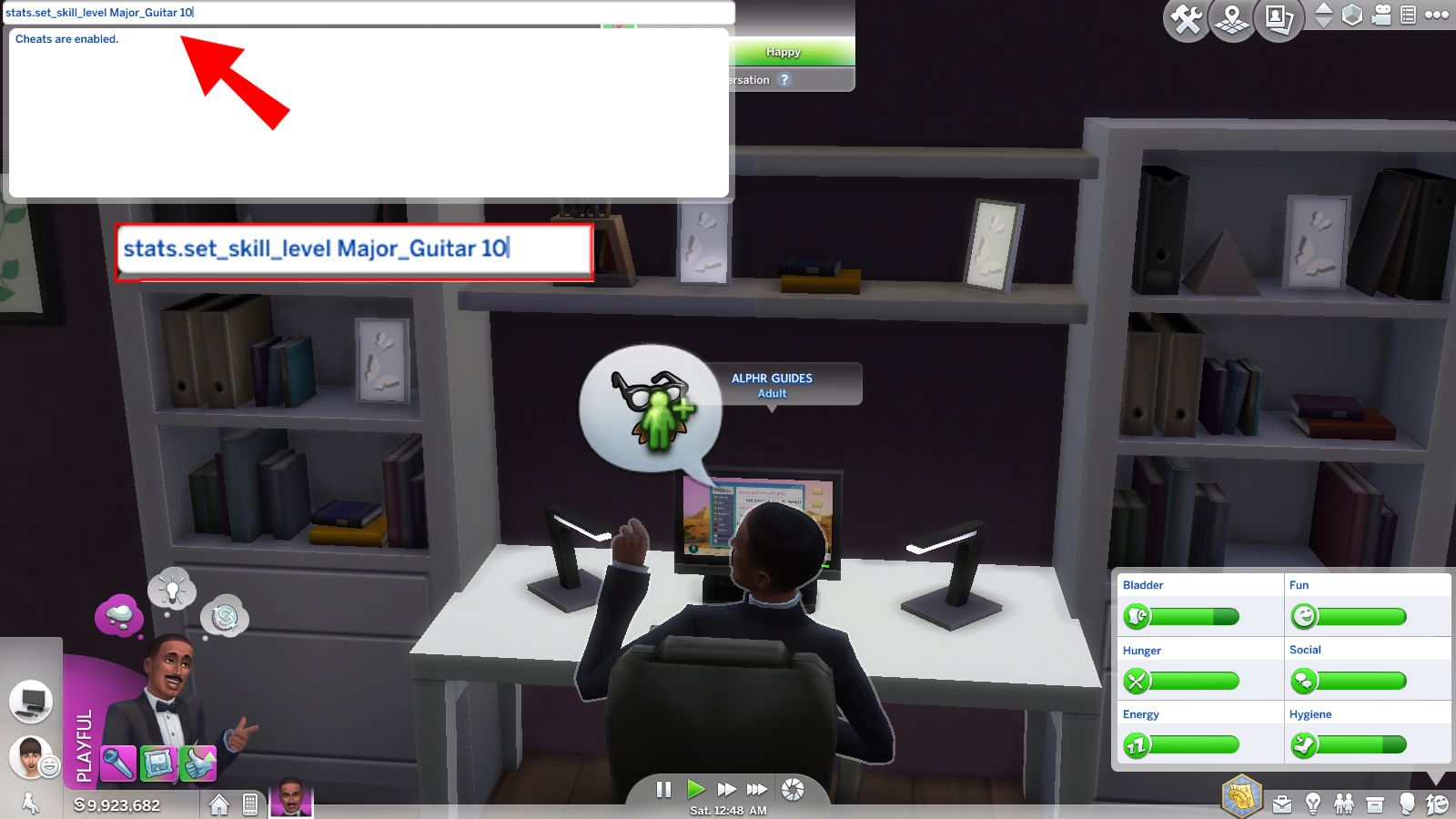

- In the game, bring up the cheat input box. On a PC, use Ctrl + Shift + C. On consoles, press all triggers on your controller at once.

- Type in testingcheats true, then hit Enter.

- Bring up the cheat input box again and type in stats.set_skill_level Major_(skill) (desired skill level). So, to reach level 10 of guitar skill, you will have to type stats.set_skill_level Major_Guitar 10.

- To speed up the songwriting process itself, you will have to use mods. Install one of the mods for faster songwriting available online (for example, Mod The Sims- Faster Songwriting) and run the game using it.

How to Put Your Own Music in Sims 4?

Any game is better with music that fits your preferences. To add custom music to Sims 4 on a PC, follow the steps below:

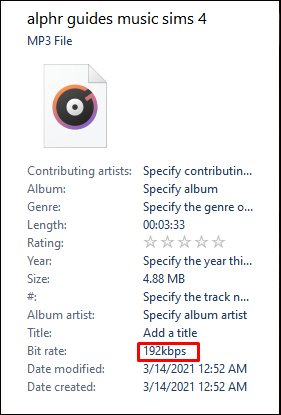

- Make sure the file you want to add to the game is in .mp3 format and doesn’t exceed 320kbit/sec.

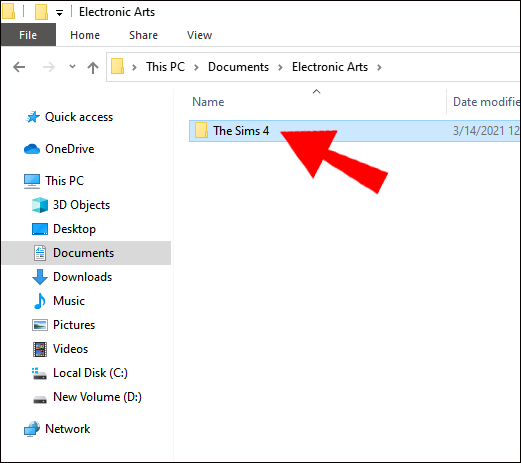

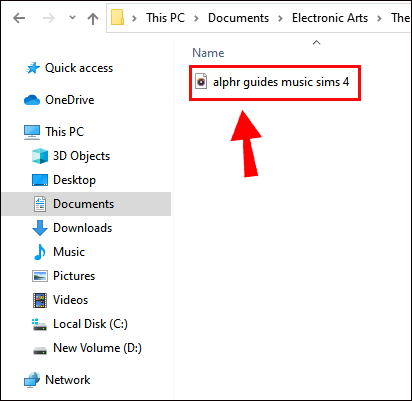

- Navigate to your Documents, then to The Sims 4 folder, and open the Custom Music folder.

- In the Custom Music folder, select a subfolder of the radio station you want the song to play at.

- Move the .mp3 file to the radio station subfolder.

- Open the game and turn on the selected radio station to find your custom music.

Tip: you can remove existing songs from radio stations in the Game Settings menu.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Do Sims Write Music in Sims 4?

Writing songs in Sims 4 is easy – you don’t need a real-life musical talent to do it. Sims play songs you select from pre-uploaded options on their own. The process takes 12 in-game hours, so you may want to take care of your Sim’s needs first.

However, you can pause the process and resume it from your inventory. If you want to take a break, you can simply click on the instrument and select Write Song, you will start recording from the beginning.

How Do You Get Custom Music in Sims 4?

Even though you can’t write custom music in Sims 4, you can upload it from your device. To do that, make sure the file you want to add to the game is in .mp3 format and doesn’t exceed 320kbit/sec. Then, navigate to your Documents, then to the Sims 4 folder, and open the Custom Music folder.

In the Custom Music folder, select a subfolder of the radio station you want the song to play at. Move the .mp3 file to the radio station subfolder. Open the game, then turn on the selected radio station to find your custom music.

How Do You Make Your Own Song in Sims 4?

Unfortunately, making your own, custom song in Sims 4 isn’t possible. You can only choose songs available in the game.

How Do You License a Song in Sims 4?

If you’d like to earn money from songwriting in Sims 4, you can license your songs. To do that, write a song and make sure you have reached level nine of the musical instrument skill.

Navigate to the mailbox of your Sim and click on it. Select License Song, then choose an instrument and a song among suggested. You will start getting royalty payments the next morning. Payments last for a week. During this period, you won’t be able to write songs using the same instrument.

What Is the Best Mood for Writing a Song?

Your skill points will grow faster if you practice in the right mood. Ideally, your Sim has to get inspired before playing a musical instrument. To get inspired, try to take a thoughtful shower, admire art, or choose the Creative trait to find random inspiration.

What Are the Best Traits for a Musician Sim?

If you want to pursue a successful career in music, choose the right traits for your Sim. The Creative trait will affect how often your character gets inspired. If a Sim is inspired while playing a musical instrument, they will gain skill points faster.

The Music Lover trait is helpful, too – your Sim will get a mood boost every time they listen to or play music. To gain even more skill points from practicing, select the Musical Genius aspiration among the bonus traits.

How Can I Earn Money From Songwriting in Sims 4?

There are several ways to earn money from songwriting in Sims 4. The first option is to license a song and get royalties. However, you only get royalties for a week, and only for one song per instrument during that time. To earn more, you can master playing several instruments at once.

The second way to earn money from songwriting is to get tips from playing in public places. Finally, with the Get Famous extension, you can sign with a record label.

How Do the Musical Instrument Skill Levels Differ?

At level one, your Sim only starts practicing the chosen instrument. At level two, the Sim can research the instrument and appreciate music played on it when listening to the stereo. At levels three to seven-, your Sim learns how to play more musical genres on the instrument.

At level eight, you unlock the songwriting option and can play classical songs. At level nine, you get to license your songs and get royalty payments. When you reach the maximal skill level, you can become a mentor.

Can I Write a Custom Song in Sims 4?

Unfortunately, there is no such option – you can only choose a song among pre-uploaded. However, you can add your own music to one of the Sims radio stations and listen to it at any time from the stereo. Note that you can’t create a new station.

Become a Great Musician

A musical career isn’t the easiest path in Sims 4 – it is time-consuming and doesn’t pay as much as most of the other skills. However, difficulties have never stopped truly creative personalities. Hopefully, with the help of our guide, the songwriting process in the game has become clear for you. If you are determined to become a musician in Sims 4, master several musical instruments at once, and you will achieve success.

Have you tried out the Get Famous and Get Together expansion packs? Would you like the songwriting process in Sims 4 to be faster? Share your opinions in the comments section below.

Disclaimer: Some pages on this site may include an affiliate link. This does not effect our editorial in any way.