WhatsApp Groups are excellent ways to share news and bring friends and family together. They can also be a great source of information about your favorite brand or blogger. But if you’re new to WhatsApp or not particularly tech-savvy, you might not know how to join different groups.

Fear not. You’ve landed on the right page. Whether you’re searching by name or ID, we’ll help you find exactly what you’re looking for. Plus, we’ll share tips on finding group members and admins in any WhatsApp group.

How to Find WhatsApp Group by Name

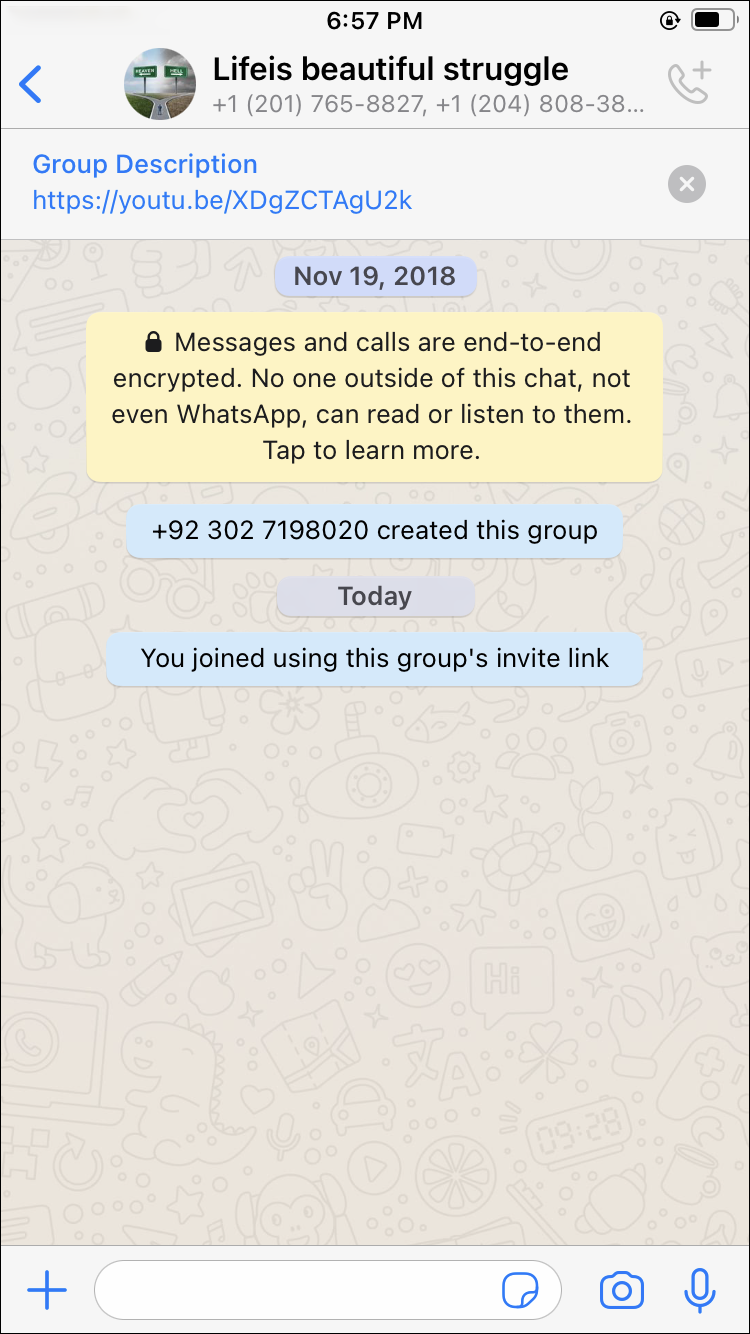

Let’s get some things clear first. If you’re a WhatsApp user, you can only find private or public groups on WhatsApp if you are already in them. On the other hand, it’s impossible to find a private or public group you’re not a member of unless the admin sends you an invitation.

If you’re looking for a group you’re already in on WhatsApp, here’s how to find it.

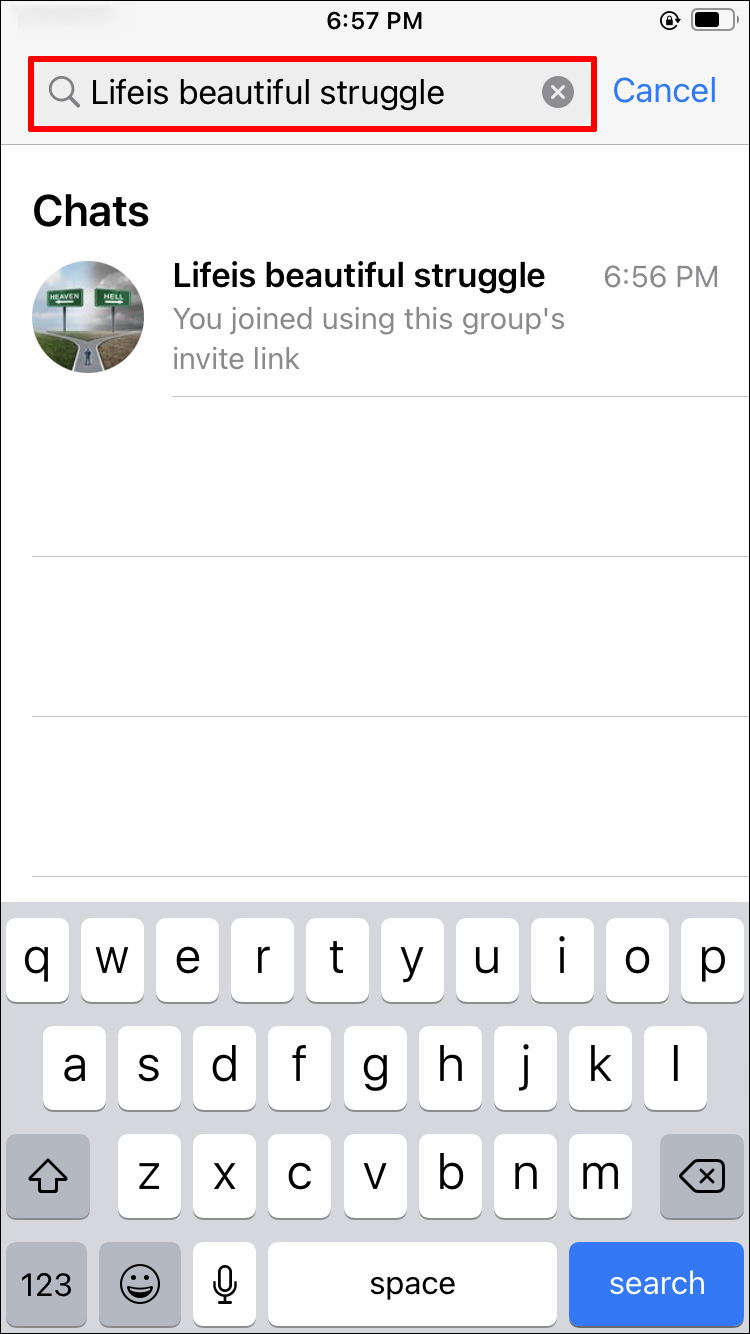

- Open WhatsApp on your iOS or Android device.

- Tap on the search icon at the top of the screen.

- Type in the name of the group you’re looking for.

- The matching results will appear in the results.

- Tap on the group to access it.

Finding groups that don’t require admin permission for you to join is possible. You can do so via third-party apps. However, unless you’re certain you can find a specific group this way, we don’t recommend using these apps often. Many users report concerns about receiving group invitations asking for sensitive content after joining these apps.

If you’re okay with this, proceed with the steps below.

iPhone or iPad Users

WhatsApp lets iPhone and iPad users connect to third-party apps to explore different public groups and join them without an invitation. Before installing these apps, please note that their source isn’t always trustworthy. One of the most popular apps on the App Store for finding WhatsApp groups is “Groups for WhatsApp.” Here’s what you need to do:

- Go to the App Store and install “Groups for WhatsApp.”

- Open the app and connect your WhatsApp account to it.

- Search for groups you wish to join. You can choose between different categories as well as recently active groups.

- Tap on the “Join” button to enter.

Android Phone or Tablet Users

Android users can choose from a limited number of apps on the Google Play Store that offer databases to tons of WhatsApp groups to join. Sadly, there don’t seem to be any “really good” Android apps available that provide joinable WhatsApp groups. In fact, most are copies and many have functional issues.

The option with the best reviews and updates is “Whats Group Links Join Groups” by Shaheen_Soft. Ensure you get the right one, which is why we provide the developer’s/submitter’s name. The app isn’t perfect, just like any other. However, it is certainly better than most that get released. It’s apparent that the app isn’t U.S.-based, but it’s one of the few apps that actually have a good rating. To mute ads, tap the speaker in the bottom-right section.

Note: No matter which WhatsApp Group apps you install and use, be cautious since some may be malicious or include security/privacy risks, and most also include adult ads in the mix. In addition, the chats have the possibility to become vulgar or disturbing.

Here’s how to use Whats Group Links Join Groups.

- Go to the Google Play Store and install the “Whats Group Links Join Groups” app by Shaheen_Soft.

- Once launched, view the Disclaimer about compliance and guidelines, then tap “Accept.”

- Tap on “Group Links” or “Categories” to browse groups.

- Tap the “Join” button for any group you want to join.

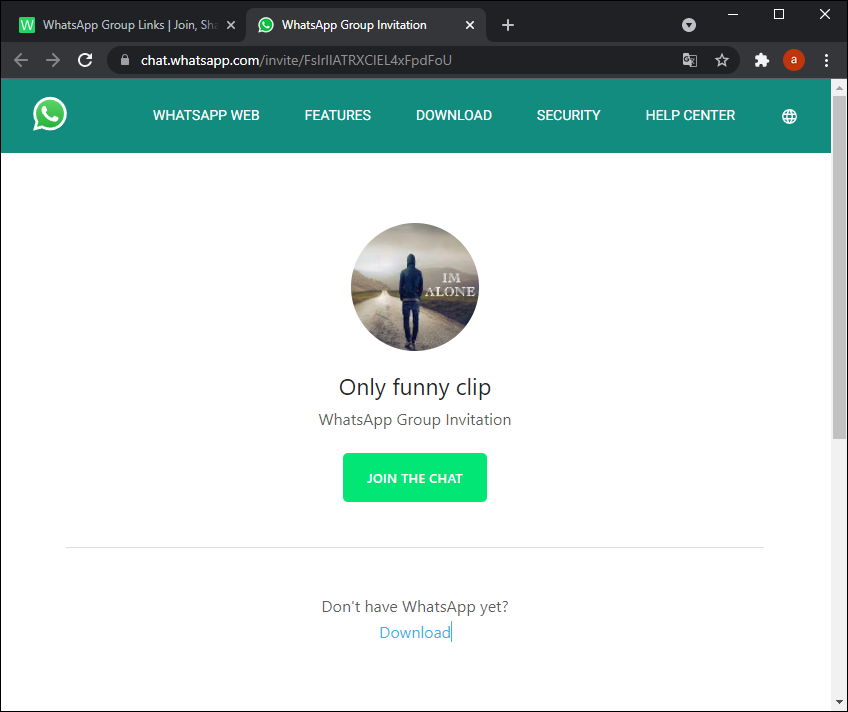

- The webpage loads in your default browser. Select “Join Chat” and go from there.

For PC Users

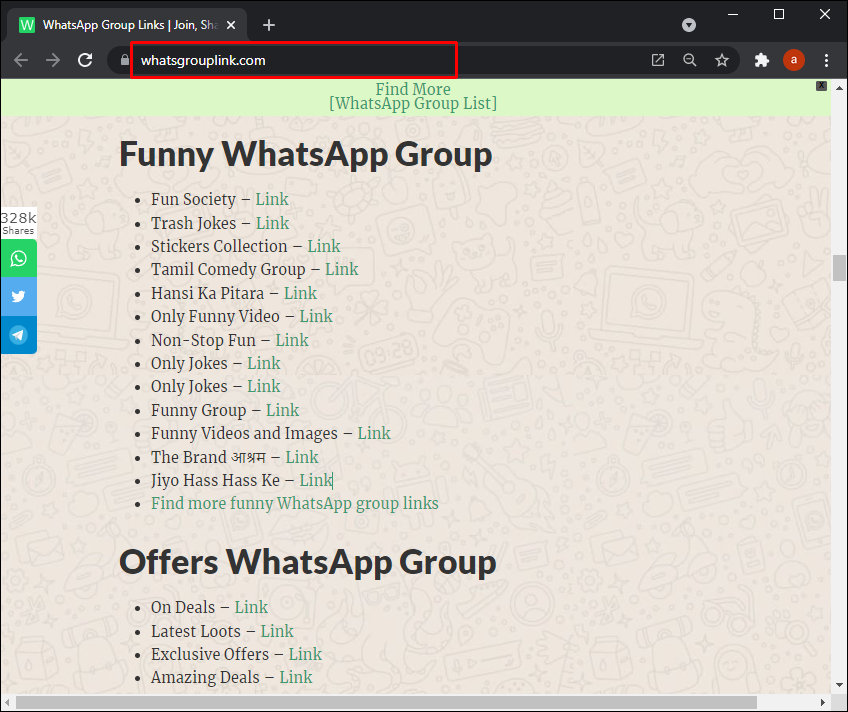

If you use WhatsApp on a PC, some great websites are explicitly created to post links to WhatsApp groups for everyone to join. This is, by far, the best solution. Just do a Google search for terms like “WhatsApp group links” or “WhatsApp groups to join,” or follow the steps below.

- Go to the WhatsApp Group Links website.

- Select a group topic for the group you want to find.

- Click “Join WhatsApp group.”

As you browse through the website, you’ll see a list of the latest group invite links, as well as category-sorted links. Use the “Ctrl + F” or “Command + F” keys to look for the groups you want.

Alternative Methods to Finding WhatsApp Groups

There are tons of ways to find WhatsApp groups online. For example, go to Facebook and search for “WhatsApp groups,” then choose the “Groups” filter. You can do similar research on platforms such as Tumblr or Reddit. Do be mindful, before joining any WhatsApp groups you find online, that they may not have great moderation, and you may subject yourself to NSFW or spam content.

How to Find WhatsApp Group ID

Finding the WhatsApp group ID is straightforward if you’re a group admin. Otherwise, you should ask the admin to do the following for you:

- Open WhatsApp on your Android or iOS device.

- Navigate to the group which ID you want to find.

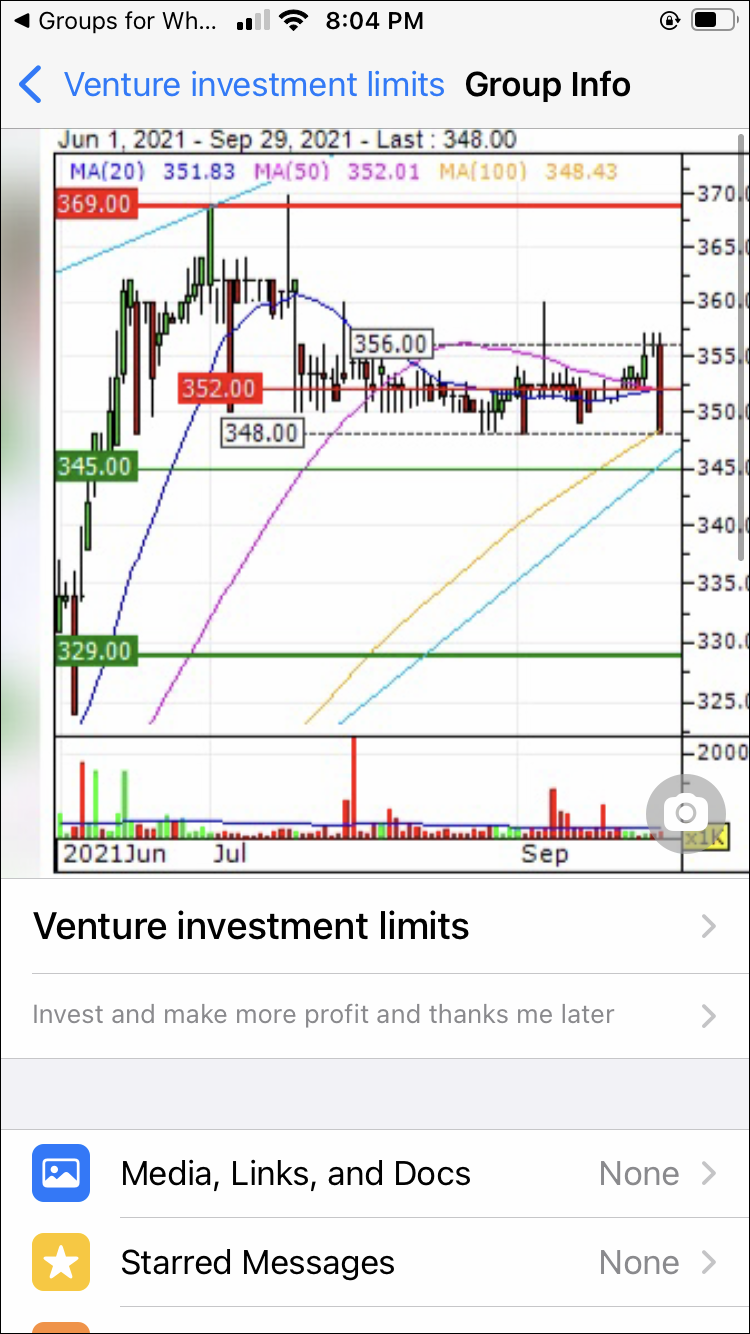

- Open the “Group Info” section by tapping on the group name at the top of the screen.

- Tap on the “Invite via link” option.

- The suffix part of the link is the ID of the group. You can copy and share the group ID link or create a QR code for people to scan and join.

How to Find a WhatsApp Group Admin

Maybe you just joined a WhatsApp group and want to contact or see who the admin is. It’s relatively easy to find the owner of the group on WhatsApp. Just follow the steps below:

- Open WhatsApp on your Android or iOS device.

- Navigate to the group where you’re looking for an admin.

- Open the “Group Information” page by tapping on the group name at the top of the screen.

- Go through the members’ list by scrolling the page.

- The group admin will have a small “Group Admin” box next to their name. They are typically placed in front of other users at the top of the list. There can be multiple admins, so don’t be surprised to see a few names with the admin badge.

How to Find WhatsApp Group Members

Finding group members in a WhatsApp group is super easy. You have to open the “Group Info” page and scroll through it. If you need further assistance, follow the more detailed instructions below:

- Launch WhatsApp on your smartphone.

- Tap on the group thread for which you want to find members.

- Tap on the group’s name at the top of the screen to open the “Group Info” page.

- Scroll down to the “Participants” section.

You can now see how many group members are in the group and who they are. The group administrators will show first with an “Admin” badge next to their name. The rest of the members will go under them in alphabetical order. If you want to search for a specific group member, tap on the search option next to the participants’ list. Just search for the person by phone number or username.

Frequently Asked Questions

Here are the answers to more questions you may have about WhatsApp.

How do I invite my friends to a group?

If you’re a group member and have permission to invite friends, all you need to do is open the chat and tap on the group name at the top. Then, tap Invite to Group Via Link. Copy the link to your device’s clipboard and share it with your friend.

Why can’t I create a group?

If you don’t see the option to create a WhatsApp group, it’s probably because WhatsApp doesn’t have access to your contacts.

How many people can join a WhatsApp group?

A WhatsApp group can have 256 members.

Navigating WhatsApp Groups

WhatsApp is great for joining groups and getting closer to your friends and family. If you’re in the mood to join public groups, you can also find those. Just note that the app doesn’t have a built-in search engine to search for the latter. You have to use third-party apps or online databases.

Hopefully, after reading this article, you can find any group on WhatsApp you want. Also, you should now know how to find group admins, group IDs, and group members.

Did you use any of the third-party resources to find public WhatsApp groups? What groups do you typically join? Share your thoughts and experiences in the comments section below.9004

Disclaimer: Some pages on this site may include an affiliate link. This does not effect our editorial in any way.