Device Links

Are you tired of third-party apps compressing photos you’re trying to send through email? Although the message may look fine on your end, the app has compressed your files, and the recipient is receiving low-quality pictures. Fortunately, you can email photos from your iPhone or Android device and share them without worrying about image compression.

Keep reading to learn more.

How to Email Photos From an Android Device

Instead of sending a photo through an app and degrading its quality, you can email it from your Android phone and ensure it stays sharp and clear. Here’s what you need to do:

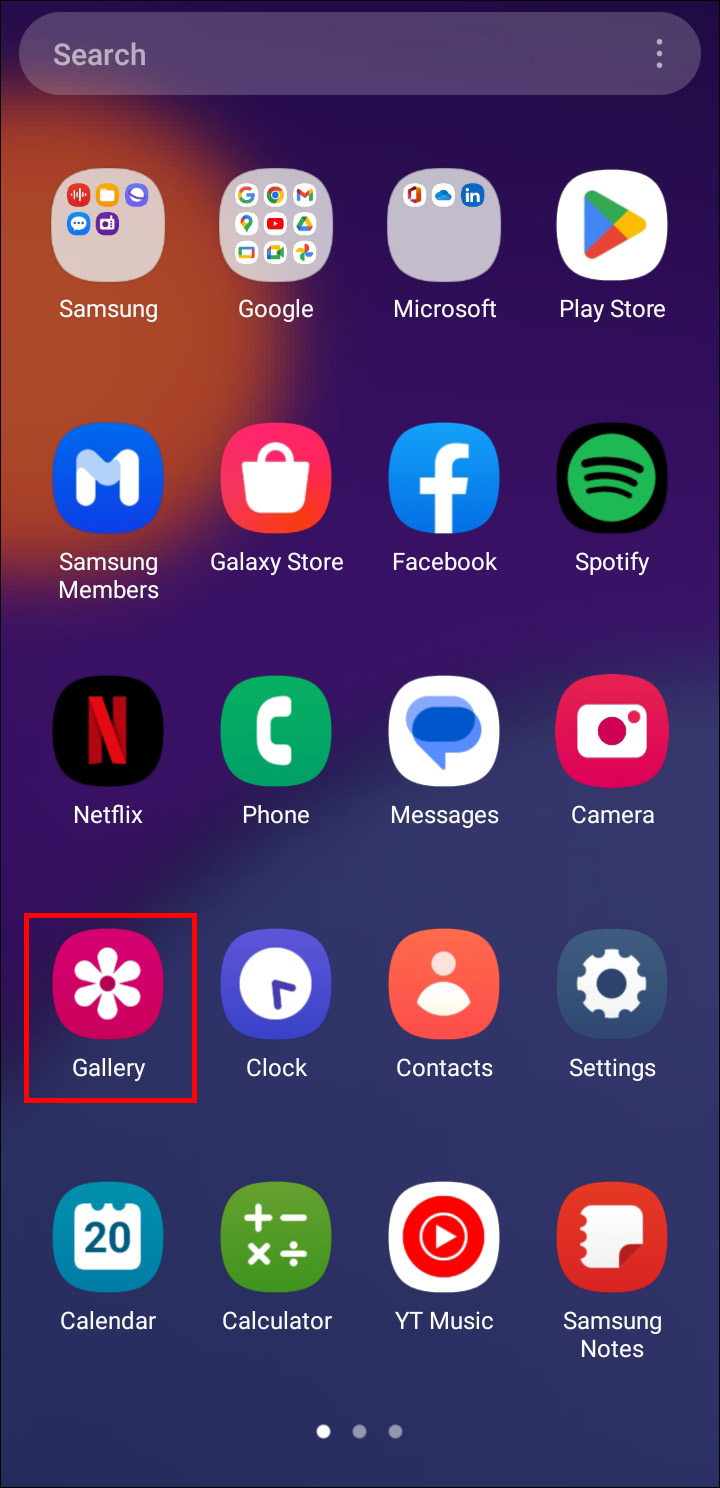

- Open the Photo Gallery on your device and locate the picture you want to send.

- Select the small “Share” button in the lower left of the screen to view your digital accounts.

- Select your email account from the list of options.

- The new screen will display photos stored on your device.

- Tap “Next” to move on.

- Enter the recipient’s email address in the email window.

- Hit “Send” in the top right of the window.

You can also send multiple photos from your Gallery. The process is relatively quick and easy.

- Open your smartphone’s Photo Gallery and tap one photo you wish to send.

- Click on the “Share” button in the lower right to see the digital accounts associated with your device.

- Tap your email account, and the photos saved on your phone will appear in a new window.

- Go through the pictures and select the ones you want to attach to the email.

- When you’re ready to move on, press the “Next” button.

- Type the recipient’s email address in the appropriate field.

- Tap “Send.”

If you’re struggling to locate specific photos, you may not have taken them with your phone’s camera, so that’s why they’re not in your Gallery. Your phone has probably stored downloaded photos and files received through Bluetooth in the DCIM folder.

How to Email Photos From an iPhone

Your iPhone can snap high-quality photos, and you can share them with friends and family by shooting them an email in just a few clicks.

Here’s how you can email a photo from your iPhone:

- Tap the colorful flower-like icon to launch the Photo app.

- Press “Select” in the top right of the screen and choose the photo you want to send. (If you can’t see “Select,” tap the picture to view the available options.)

- Pick the share icon in the lower-left corner of the screen and click “Email photos.” (Depending on the model of your device, you may need to select “Next” before pressing “Mail.”)

- Add the recipient’s address in the “To:” field.

- After constructing the body of your email, press “Send” in the upper right of the window.

Attaching multiple photos to an email on an iPhone is straightforward and allows you to share your memories with others in high resolution. Follow the steps below to do so:

- Press the multicolored flower-like icon to open the Photo app.

- Tap “Select” in the top right corner of the app and click the photos you want to send.

- Choose the share button in the lower left and hit “Email photos.” (On some iPhone models, you may need to tap “Next” before clicking “Mail.”)

- Construct your email and enter the contact in the “To:” field.

- When you’re satisfied with the message, hit “Send” in the upper right.

On some iPhones, the “Select” option may not appear. Here’s what you should do in those cases:

- Click the flower icon to open the Photo app.

- Tap the photo you want to send and press the share icon in the lower-left part of the screen.

- Select the “Email photos” option. (On some iPhone models, you need to tap “Next” before clicking “Mail.)

- Repeat the above process until you’ve selected all the photos you want to email.

- Fill out the email and add the recipient’s address in the “To:” field.

- Press “Send.”

Send High-Quality Photos With Ease

You don’t have to download battery-draining apps to send photos without damaging their quality. Instead, you can rely on your trusty iPhone or Android device and quickly attach your photos in an email. Adding multiple files to the message is straightforward, so you won’t have to waste time sending several emails to deliver your pictures.

Have you emailed photos from your Android or iPhone device before? Which of the above methods did you use? Let us know in the comments section below.

Disclaimer: Some pages on this site may include an affiliate link. This does not effect our editorial in any way.